What is architecture?

People in the software world have long argued about a definition of architecture. For some it's something like the fundamental organization of a system, or the way the highest level components are wired together. My thinking on this was shaped by an email exchange with Ralph Johnson, who questioned this phrasing, arguing that there was no objective way to define what was fundamental, or high level and that a better view of architecture was the shared understanding that the expert developers have of the system design.

A second common style of definition for architecture is that it's “the design decisions that need to be made early in a project”, but Ralph complained about this too, saying that it was more like the decisions you wish you could get right early in a project.

His conclusion was that “Architecture is about the important stuff. Whatever that is”. On first blush, that sounds trite, but I find it carries a lot of richness. It means that the heart of thinking architecturally about software is to decide what is important, (i.e. what is architectural), and then expend energy on keeping those architectural elements in good condition. For a developer to become an architect, they need to be able to recognize what elements are important, recognizing what elements are likely to result in serious problems should they not be controlled.

Why does architecture matter?

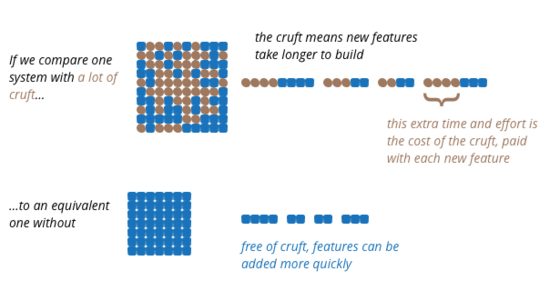

Architecture is a tricky subject for the customers and users of software products - as it isn't something they immediately perceive. But a poor architecture is a major contributor to the growth of cruft - elements of the software that impede the ability of developers to understand the software. Software that contains a lot of cruft is much harder to modify, leading to features that arrive more slowly and with more defects.

This situation is counter to our usual experience. We are used to something that is "high quality" as something that costs more. For some aspects of software, such as the user-experience, this can be true. But when it comes to the architecture, and other aspects of internal quality, this relationship is reversed. High internal quality leads to faster delivery of new features, because there is less cruft to get in the way.

While it is true that we can sacrifice quality for faster delivery in the short term, before the build up of cruft has an impact, people underestimate how quickly the cruft leads to an overall slower delivery. While this isn't something that can be objectively measured, experienced developers reckon that attention to internal quality pays off in weeks not months.

No comments:

Post a Comment